The New Future

Melika Shafahi: ‘The new future’ – toward an esthetic of associations

Text: Amin Moghadam, Ryerson university, Toronto

Private view: Friday 11 June, 2021

At a time when the lines between real and virtual are increasingly blurred, the latter may appear to be more and more the defining structure of our social condition. But the risk is that by attaching too much importance to it, we end up trapped inside. Melika Shafahi’s exhibition of photographs and videos in Tehran invites us instead to shift our gaze joyfully towards one of the noblest features of artistic creation: its ability both to grow out of encounters, and stimulate new ones.

The associations Melika evokes have their roots in her own background, between Iran and France, but also in diverse geographical locations she brings into connection through her perceptions of human relationships and how the material environment interacts with them – in this case the Friche de la Belle de Mai, a former tobacco factory converted into a cultural complex in Marseilles, France, where she was an artist in residence in 2018/2019, and her many trips to the island of Hengâm, in southern Iran.

Yet the strength of her work lies particularly in the way she blurs the boundaries between these diverse locations, as she devises an entirely new universe for her subjects to participate and perform in. Her images and objects, often taken out of their original context and scattered here and there, create an imaginary, timeless space that becomes a playground she invites us all to enter.

In Marseille as on Hengâm island, Melika leads a game for two or more with the subjects she brings into play. The winner is not decided in advance – and isn’t always the artist.

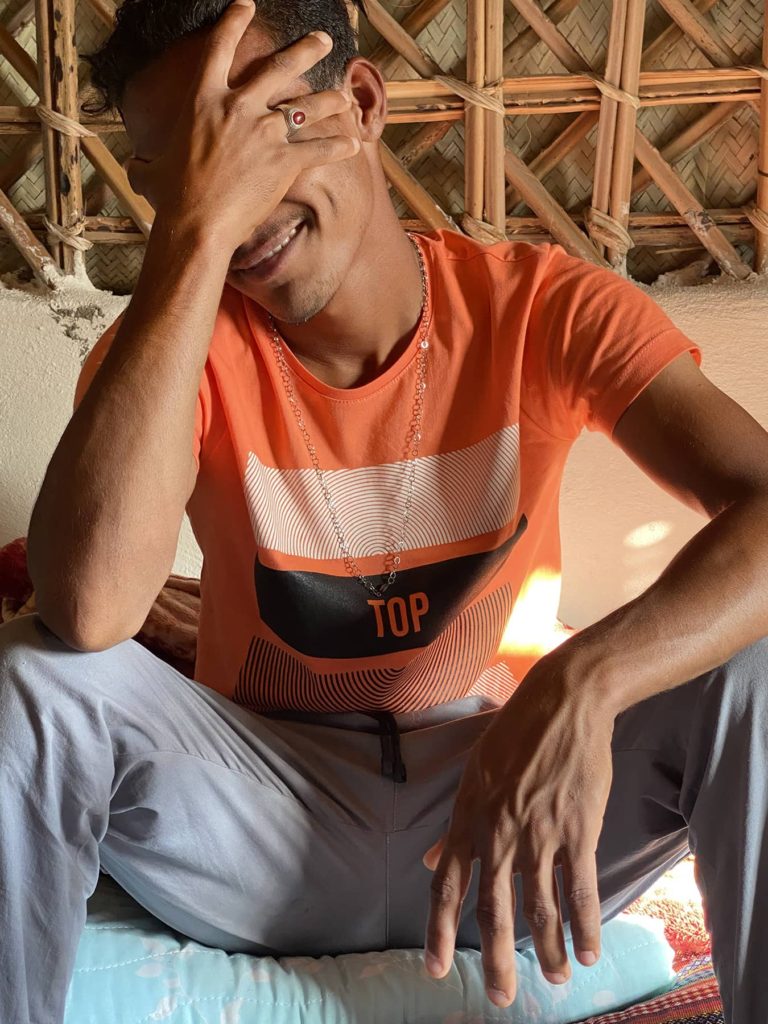

In the ‘Rapproche!’ Series from Marseille, powerful young teenagers dominate the frame from a height, in the same way as they dominate their habitat at La Friche. The objects chosen and the fabrics and garments they wear in the photos are from some other place, but we cannot tell exactly where – any more than we can with the adolescents themselves. Melika transports them away to liberty, far from the pressures of society, as if supernaturally: Alin, Kannelle, Alvina and the others…

Delighted and moved by the youngsters’ vitality, Melika bestows on them new means to act and behave as they face the camera: more feet, a bicycle, a microphone… all together, in the centre, overlooking the arena lying before them: their territory.

She highlights their ‘nowness’, with none of the stigmatizing stereotypes a narrow political viewpoint might impose. ‘One of the girls wore a veil later on, but she carried on singing and dancing to rap. This new generation of kids from immigrant backgrounds are ahead of us on many things,’ notes Melika, talking about her time at La Friche. ‘Frankly, some of them couldn’t care less about seeing the artists at La Friche. They’d already seen plenty, it was nothing new.

Some didn’t want to join in, or else they were minors and I had to talk to their parents and explain what my work was about. It was a real challenge for me to get them involved, and I enjoyed that. I lived at La Friche myself, and that gave me the chance to live alongside them. If I’d just been going in to the studio in the morning and leaving for home again at five, it would never have been the same.’

So Melika had to work on building a rapport and developing a relationship of trust with the teenagers. She took them into her workspace in the studios at La Friche, and showed them all the paraphernalia used in the creative process, ‘the big studio flashes, for example,’ without knowing in advance how they might react or whether she would succeed in winning them over. Eventually, Melika’s efforts paid off: she did manage to develop a relationship of trust. But at the same time, the process forced her to think more deeply about what it means to be an artist among other people, and the frontiers that define the scope of artistic practice.

‘Like many other contemporary art complexes, the Friche de la Belle de Mai presents itself as a meeting place, a cosmopolitan space open to the outside world. In fact,

the people who really count, who are visible and welcome, are the artists and their circles of friends. But for me, it was the kids playing in the courtyard who really gave the Friche its charm, while the studio doors were closed to them.’

This is one of the ways Melika Shafahi’s exhibition proposes a ‘new future’ – one where the frontier between the artist and society is no longer an impenetrable wall but becomes a place conducive to encounters. ‘The New Future’ evokes frontiers in the most natural way, with a colour or fabric recalling other places without Melika limiting, imprisoning or stigmatising them through ‘othering politics’. In this way, she helps meet the need to ‘de-exceptionalise’ the artistic space, in an approach which nevertheless, as it highlights the authenticity of the situations and subjects it presents, inevitably recalls the singularity of the artist and the originality of her work. The flipside of taking this kind of ethical approach is the artist’s nagging doubts and constant questioning, fuelling the energy behind her work – how she looks at others and they, in turn, see her. ‘There’s one photo I left out in the end. I had the impression I was reproducing the relations of dominance between black and white, between myself as an artist and the people in the scenes I was staging.’

Melika thus strives to capture humanity in all its complexity, both what it offers to the camera and what it forgets: ‘They’d forgotten I was there,’ she says with surprise, talking about the teenagers she met during her first stay on Hengâm island, to illustrate the degree of mutual trust she realised they had already achieved.

Relations are forged not only in the real world, but also in imaginary ones. Melika leads her characters into a dream world, the world of her own dreams. ‘When I was working with them, I often thought of the stories I used to read when I was little. The characters were black and one of

them was Queen. She was strong and powerful and full of character, like this little nine-year-old girl who was so comfortable with her body. She could have been an actress!’

Agreeing, herself, to disappear altogether, Melika brings her characters to life through her lens as they lead her by the hand into their own world, this time on Hengâm island, in a ‘close-up’ that captures both the dreams and the suffering of the other, in an environment belonging to them, a territory they master. Fake and authentic are blended together. No matter if they are from here or elsewhere, native or displaced, speaking the language of this place or the other shore.

At the same time, Melika takes them out of their usual habitat, partly without their even realising. ‘I wanted them to start making connections and associations with the images they had in their hands. They’d say, for example, “Ah, that’s the Strait of Hormuz” or “Ah, that’s Hengâm” when in fact they were looking at the pink lagoons in Mexico.’

These imaginary associations instigated by the artist nevertheless invite us to question the history of a place. ‘This picture in our hands looks like where we live,’ they told her. Yes, a Caribbean island. As if to remind us we were all global at one time. You, and those living on other shores. To show us what history can do to the spaces we inhabit.

The autonomy the objects in the Hengâm photos acquire is the result of the long journey taken by the artist, the story she has written over the course of multiple encounters, of her personal struggle to avoid duplicating too ‘exotic’ a vision, of questioning and self-questioning, as a member, herself, of a diaspora, challenging relationships of power and domination.

And so there emerges a material culture in which the objects speak for themselves: a boat trailer, a jellyfish slithering in Hossein’s palm, battered lamps, blue tarpaulin, garlands, a blanket patterned with roses, palm fronds, bits of plastic or cloth abandoned or draped on a bush…

The images she handed out to invoke voyages of the imagination now disappear, as we are drawn by its poetry into Melika’s own world. The objects become the main players in Melika’s

viewfinder, reflecting the diverse aspects of island life. ‘Je t’aime’ captures an instant: the heavy, humid atmosphere, the shock of the hot wind in your face, the light, reflecting the rhythm of daily life in this insular space, and a time of day when the twilight softens the austerity of the baking cement and tumbling lampposts, and ‘I love you’ rhymes with the crumbling concrete blocks.

Talking about her video from Hengâm island, Melika remarks, ‘They’re happy in the video. We might think they’re unfortunate, but in fact only the tourists are out of place there. The islanders drop a net in the sea and in no time at all haul out twenty fish. Whether it’s for fish or smuggling, the sea’s vital, like a mother to them. Hossein, the boatman, plunged his hand in water and pulled a jellyfish out: he can see into the water – we only see the surface beauty of it.’

In fine, Melika loves the performance of beauty, in whatever form it takes: the ‘beautiful people’ of her previous series 2014 as much as the genuinely beautiful ones in these new works.

And What if? Alvina by the wall in « Je t’aime » in Hengâm and Hossein at La Friche de la Belle de Mai in Marseille: a whole new world of possibilities, the world of a « new future ».

Tehran,Iran, 2021.

Tehran,Iran, 2021.

Tehran,Iran, 2021.

Tehran,Iran, 2021.